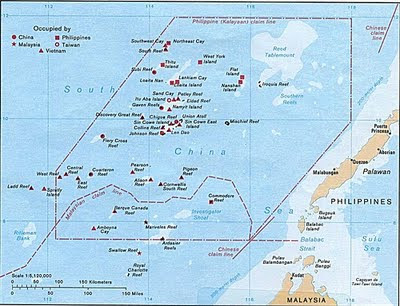

It is relatively easy for any government, like the Philippines or China, to claim territorial sovereignty over an island or group of islands such as the Spratly Archipelago in the South China Sea. What complicates this claim is the uncertainty as to how many islands, cays, reefs and atolls are actually present since many remain submerged at high tide, thus making it more difficult even to confirm their presence or exact locations.

|

| Map of Spratly Islands. Photo courtesy of Centre for International Development. |

But no matter, several countries have staked out their claims on this group of islands in South China Sea, notably among them, the Spratlys, now the most hotly contested offshore seabed resource in the region. Those who have claimed sovereignty over Spratlys are Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.

U.N. Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS)

Spratlys is at the centre of the world’s busiest sea lanes in the region and widely presumed to be rich with oil and other mineral resources such as hydrocarbons underneath and around the islands. The various claims stem largely from jurisdictional rights as set out in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS).

But the UNCLOS is not fully determinative because there are conflicting claims of sovereignty over the Spratlys. Under UNCLOS, the country that holds valid legal title to sovereignty over their islands has exclusive right to exploit living and nonliving resources within twelve miles of their territorial sea and 200 miles beyond, known as the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Sovereignty issue

One must understand that even if Spratlys is within the Philippines’ EEZ from its coastline, it is not enough to acquire jurisdictional rights. It must first satisfy the sovereignty conundrum.

Does the Philippines or any of the other claimant states have legal title to sovereignty to Spratlys? This is the crux of the problem. At the core of Spratlys dispute is the question of territorial sovereignty, not law-of the sea issues. If the issue of sovereignty can be resolved, then the maritime jurisdictional principles codified under UNCLOS can be applied to the Spratlys.

At present, no claimant government has yet established sufficiently substantial legal grounds to validate its claim over Spratlys. China, the wealthiest and with the most military clout in the region, has been traditionally opposed to multilateral negotiations with its rival claimant countries, primarily because its sovereignty over the islands is held as non-negotiable, although it has been willing to negotiate joint ventures for exploiting natural resources in the area bilaterally.

Obviously, China’s position is self-serving since it can be outvoted by the other countries in the dispute if the issue of sovereignty is put on the table, thus putting the situation in a stalemate. The possibility of resorting to military action by the rival states to defend their claims has already started, albeit on limited scale, but could potentially exacerbate an already protracted problem.

The countries more assertive of their claims over Spratlys are China, the Philippines and Vietnam. Their respective claims are based on acts of discovery, occupation and more recently, by way of the UNCLOS, on certain inferred rights over continental shelf delimitation. When the prospects for petroleum exploration became real during the 1970s, the 1982 UNCLOS appeared as the standard for demarcating offshore jurisdictional limits for resource exploitation.

China’s historical justification

China’s claim of territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea rest on historical claims of discovery and occupation that went back to references to the 12th and 18th centuries during the Sung Dynasty and Qing Dynasty, respectively. There are, however, problems of authenticity and accuracy in describing references for the Spratly Islands. The China case is further compounded by the fundamental question of whether proof of historical title today carries much legal weight to validate acquisition of territory.

|

| Chinese map of Spratly Islands. Photo courtesy of Joe Jones. |

The Philippine claim: Discovery and occupation

The Philippines justifies its claim to the Spratlys on discovery and occupation by Tomas Cloma, an enterprising Filipino businessman and owner of a fishing fleet and a private maritime training institute. Cloma aspired to build a cannery and develop guano deposits in the Spratlys. Until World War II when there was no mention yet of potential mineral deposits in the Spratly Islands, the Chinese considered the islands in the South China Sea as having no precious value to them and were only worth their weight in guano.

In 1947, Cloma established a settlement on eight islands of the Spratly Archipelago. He declared himself protector of the islands in 1956 and named them Kalayaan Islands (Freedomland). Then, Cloma deeded the Kalayaan Islands to the Philippines in 1974, after which President Ferdinand Marcos formally declared Kalayaan Islands as part of the Philippines and placed them under the administration of Palawan province. Quite interestingly, the official Philippine position asserts that the Kalayaan Islands group are separate and distinct from the Spratlys and Paracels. This claim is based on a geological assertion that the continental shelf of the Kalayaan Islands group is juxtaposed to the Palawan province and extends some 300 miles westward, into the heart of the Philippines’ EEZ.

Vietnam: History and continental shelf principle

Vietnam’s claims are based on a combination of historical data and the continental shelf principle. According to Vietnamese court documents during the reign of King Le Thanh Tong in the 15th century, the Vietnamese claimed sovereignty over the Spratly Islands. This claim was well documented during the 17th century when Vietnamese maps incorporated the Spratly archipelago into Vietnam. In 1884, the French established a protectorate over Vietnam and asserted their colonial claim to the Spratly and Paracel island groups. Ironically, the present Vietnamese government continues to use these historical claims to justify their sovereignty in the South China Sea.

Under modern international law, the mere discovery of some territory does not sufficiently vest to the discoverer valid title of ownership. Discovery only creates an inchoate title, which must be perfected by subsequent continuous and effective acts of occupation and settlement.

Evidence of permanent settlement is not compelling in the case of China’s claim to the Spratlys. There are considerable doubts as to the authenticity and accuracy of the Chinese historical records. This is why international law usually regards mere historical claims, without evident occupation and permanent settlement, as only as arguably binding and open to legal challenge in order to establish a valid claim over territory in the oceans.

Interestingly, Article 121 of the UNCLOS states that “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive zone or continental shelf.” This particular provision has been used by the claimant countries to justify attempts to build structures on submerged rocks and reefs in order to establish a new EEZ in the region. But if two countries establish structures in close proximity, then an overlapping EEZ could emerge, thus creating potential overlapping claims which may not be resolved under the law of the seas.

Spratlys a vortex of competing claims

In short, the Spratlys situation remains complicated by competing claims and the possibility of military confrontation. China, in the foreseeable future, will remain dominant throughout the South China Sea because it has the economic wherewithal, the technology and the military might to assert itself either through naval force or diplomacy. An expansionist China is being compelled by a need to support greater demands for more goods and services from its burgeoning population of close to 2 billion people, and China has already demonstrated its willingness to use military force, if necessary, to protect and support that expansion.

David vs. Goliath and R.P.-U.S. Mutual defence pact

However, the other claimant states in the South China Sea dispute will not give up easily their sovereignty claims. Fuelled by nationalistic motivations, each country perceives its sovereignty as exclusive and sacred. The history between China and Vietnam in the South China Sea has been antagonistic. Now, the Philippines, in a kind of mismatch between David and Goliath, has entered the fray and been making overtures to the United States for possible military assistance should confrontation with China become imminent.

|

| Filipino-Canadians hold picket at the Chinese Consulate in Toronto to protest China's initiative to take control of the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, July 8, 2011. Please click the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wgPcunivDXg to view Loida Nicolas Lewis, Chair of the U.S. Pinoys for Good Governance (USP4GG) speak against China's "intrusion" in Philippine waters. |

The Philippines is relying on its mutual defence treaty with the U.S. that commits American military action to defend governments within the treaty area, including the South China Sea. But the mutual defence pact between the two countries has been suspect for a long time, and whether the U.S. is under obligation to come to the aid of the Philippines in the event of an armed attack is highly dubious. Besides, if there is an armed attack against the Philippines, it should be first reported to the United Nations Security Council of which China is a permanent member. Thus, multilateral diplomacy has to be exhausted before resorting to use of reasonable force.

China to U.S.: Stay out

Will the United States take the risk of alienating and angering its principal trading partner and creditor? Again, that is very unlikely. China has already warned the U.S. to stay out of the South China Sea conflict.

But Filipino-Americans in the United States and other Filipinos in the diaspora, including in Canada, are being urged to picket Chinese consulates around the world to protest China’s apparent power grab in the South China Sea. This is fine if the purpose is to push China to accept multilateral talks among the South China Sea disputants, but not to further inflame the conflict with nationalistic claims that will not result in lasting solutions. Statements such as “China’s intrusion in Philippine waters” or “Spratlys are worth dying for,” especially coming from Filipino émigrés, are vacuous and empty. Here comes again the opportunity for Filipinos who did well abroad to make light of the real economic and poverty issues that confront their countrymen in the Philippines, by focusing on an issue that hardly matters to the average Filipino.

Not that sovereignty or our national patrimony is not an important matter, but this issue has always been sidestepped by our own leaders in government when it comes to foreign investments.

The Malampaya “10 per cent” lesson

Take the case of the Malampaya project in offshore Palawan. Former President Gloria Arroyo ignored and violated the Philippine Constitution by allowing Shell and Texaco to get a 90 per cent stake in the entire project, divided equally between them, and leaving the remainder, or 10 per cent, to the Philippine National Oil Corporation (PNOC).

Or the Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking (JMSU) signed between China, Vietnam and the Philippines in 2005? This is another clear example of a violation of the Philippine Constitution which might have been signed in exchange for bribe-tainted loans, prompting a Philippine newspaper columnist to write: “It isn’t that we sold potentially oil rich shores so cheaply, but we have bartered our souls.”

How about the current Aquino government reclaiming back our constitutional right to our natural resources, instead of making idle overtures on Spratlys over which all we have is a disputable claim to territorial sovereignty?

Waging a proxy war for the U.S.

Something smells fishy in the sudden interest of the present Philippine government and their followers abroad such as U.S. Pinoys for Good Governance (USP4GG) to engage China in the Spratlys dispute. In inviting the United States to join the fray, it looks very obvious that this is turning to be a U.S. proxy war with China on Philippine battleground.

|

| Filipino-Canadians picket the Chinese Consulate in Toronto, July 8, 2011. |

But not everything is lost yet over Spratlys. There are precedents of resource development arrangements that have been successfully negotiated in the past which could serve as models for managing resource development in the South China Sea. These arrangements also mirror the problems faced in Spratlys, issues such as disputed sovereignty, maritime jurisdiction, geostatic considerations, and access to natural resources.

Precedents worth considering

Precedents like the Australia–Indonesia Timor Gap Agreement, the Spitsbergen (Svalbard Treaty) Arrangement Svalbard for the cluster of glaciated islands in the Arctic Ocean, and the Antarctic Treaty, can provide insights and salient lessons for negotiating an arrangement that could resolve, if not at least mitigate the disputed sovereignty situation in South China Sea.

These arrangements from the past demonstrate that international agreements are possible and resource development schemes can be created—if the parties are willing to make them happen. However, no agreement would be possible absent the political will to enter into compromises. China must accept multilateral negotiations, bearing in mind that there is more than one or two disputants in the South China Sea.

Posturing from the Philippines will not help either, especially if it would only draw the United States in a proxy war with China. The mutual defence pact between the Philippines and the U.S. has outlived its usefulness, assuming it was in the past. The United States probably needs the sea lanes and the airspace in the South China Sea for its naval force to manoeuvre in protecting Japan and South Korea—two countries which should also play an active role in resolving the Spratlys dispute.

Read my comments here: http://bit.ly/nVzpSN

ReplyDelete